|

Cognitive psychologists and e-commerce consultants are quick to

point out that creativity is the ability to "think outside

the box," yet few of them are prepared to tell you what someone

thinking outside the box actually looks like. I happen to know a

pretty good picture of someone thinking outside the box: the artwork

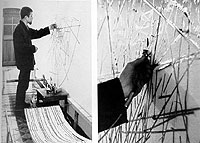

Magnet TV (1965), in which What makes Paik's intervention creative is not so much his use of technology as his deliberate misuse of it. As the artist himself put it, "Television has attacked us for a lifetime--now we strike back." In lugging a magnet onto a TV, Paik violated not just the printed instructions that came with the set but also the political assumptions underlying its widespread use. Artistic misuse exploits a technology's hidden potential in an intelligent and revelatory way. Looking at the way artists like Paik began to investigate the deliberate

misuse of technology in the 1960s helps debunk some contemporary

myths about creativity--in particular, the creative use of technology.

One of those myths is that creativity lies in applying the right

tool for the right task--i.e., managing technology. Magazine editors,

advertising execs, and Web site producers regularly employ "creatives"

to spice up their products. The assumption behind this ludicrous

adjective-turned-noun is that a creative person is simply a painter

of pictures or a teller of stories--especially one adept at While managing technology is certainly a valuable skill--for artists and others--it's not the same as creativity. When you manage technology well, you are simply carrying out the agenda of the designers of that technology. A composer who uses a car to drive to the concert hall is managing technology. But when Laurie Anderson composed a drive-in concert of motorists beeping car horns, she was being creative. To misuse technology is not just to manage technology, but neither is it to mismanage technology. There's nothing creative about broken links or glacial downloads. Misuse is deliberate. When Paik made a work for violin, he did not merely play it badly. In One for Violin Solo (1961), he raised the instrument slowly over his head and then brought it crashing down on a table, smashing it to smithereens. Mismanagement can sometimes be overlooked; misuse is unmistakable. One last strategy that's often mistaken for creative misuse is mystification. Artists who mystify technology tend to get an inordinate amount of attention from critics and curators. I'm not sure why--maybe the work replicates the intimidation they feel in the face of technology. But mystification is not misuse either. For example, most video and computer-based artworks conceal their source decks and cabling behind a gallery wall. Without access to the secrets inside this "black box," viewers are left with the presumption that the artist has conjured the images by some arcane feat of technological magic rather than by some mechanism they might understand. In his 1963 installation Random Access, Paik did the reverse: he tacked fifty-odd strips of

prerecorded audio tape to the wall, then ripped the playback head

out of a reel-to-reel deck and wired it to a pair of speakers. He

then encouraged his viewers to pick up the playback head and run

it across the audio segments whatever order they wished. In so doing

Paik exposed the inner workings of a tape player to his viewers,

giving them a hands-on feel--quite literally--for how the mechanism

worked. In the process, of course, he

Of course, technologists sometimes misuse their tools for a practical purpose. NASA engineers jury-rigged a filter out of spare parts and duct tape to save the astronauts of Apollo 13 from poisonous gases venting inside the crippled capsule. We demand more from artists, however, than a creative process--we demand that the result of that process expand the mind of its beholder. The greatest artistic contributions to new media consist not merely of new ways to arrange diodes and DVDs, but of new ways to envision the world using these tools. Creative misuse can be destructive, as in Jean Tinguely's self-destructing sculpture Homage to New York (1960). Misuse can be wrong-headed: for his 1963 performance Pelican, Robert Rauschenberg adorned dancers with one technology designed to enhance speed--roller skates--and another--parachutes--designed to impede it. Misuse can mean crossing wires, either literally or figuratively. Rauschenberg's synaesthetic performance Open Score (1966) crossed perceptual wires between the senses of hearing and vision. Here players of a live tennis game triggered an amplified "bong" and extinguished one of the auditorium's lights every time they hit the ball--thanks to a miniature radio transmitter inside each racket--until the auditorium was immersed in darkness. I've chosen examples from the 1960s, but the artistic misuse of

technology goes back to filmmakers like Charlie Chaplin, who created

cinematic effects by cranking film the wrong way through the camera.

And some of the most creative artists working today are using Internet

technologies in all the wrong ways. An outstanding example from

the mid-1990s is Jeffrey Kurland's The Dotted Line, a Web

page consisting only of an immensely long column of colored dots.

By clicking up or down on the browser's scroll bar, viewers could

animate the dots in the manner of Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope--revealing

a hidden connection between the technology of a Web browser and

the technology of the early cinema. Online collectives such as Group

Z and jodi.org exploited a bug in Netscape 1.1 to achieve certain

effects; when Netscape 2 corrected the bug these works were no longer

viewable in their original form. The technology Mark Napier's Shredder

exploits, Cascading Style Sheets, was originally intended to pin

down the elements of a Web page so that designers could specify

the same fixed page layout on different computer screens. The Shredder,

however, turns this page metaphor inside out by swapping the placement What is the ultimate effect of creative misuse? Sometimes misuse becomes the norm. In a 1976 report to the Rockefeller Foundation, Paik coined the provocative term "electronic superhighway"--a phase that Bill Clinton paraphrased in his campaign rhetoric as "information superhighway" and has since permeated public consciousness. More often, however, misuse is of no direct practical value, but does what art is supposed to do: stretch our minds to accommodate not only the box, but what's outside it as well. adaweb.walkerart.org/influx/~GroupZ Jon Ippolito is an artist and Assistant Curator of Media Arts at the Guggenheim, where he recently co-curated The Worlds of Nam June Paik with John G. Hanhardt. www.three.org

|